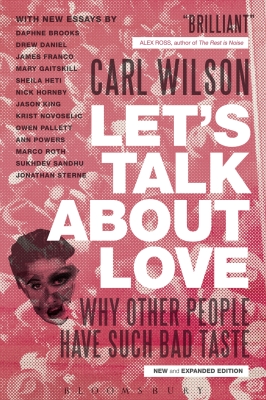

Seven years after the release of music critic Carl Wilson’s seminal exploration of Céline Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love for the 33⅓ series, the author is back with an expanded version of his 2007 text. While the original edition analyzed how we formulate and understand our tastes and biases through the lens of Wilson’s personal experience with Dion’s music and cultural dominance, the inclusion of new contributions from other noted critics in this re-release (Ann Powers, Krist Novoselic, James Franco, and Mary Gaitskill, to name a few) presents a rich dialogue from a wider range of perspectives (read: criticism of Wilson’s criticism). From his home in Toronto, Wilson answered our questions concerning his skepticism of critical distance, the shifting nature of modern taste, and the musician who’s best at making him cry.

I enjoyed the inclusion of personal bits in the book (such as your ex-wife’s relationship to Buddy Holly’s “Oh Boy”). What was your decision-making process when it came to inserting yourself into an otherwise research-heavy book?

I always knew that there would be a first-person element, as this was a cultural experiment on myself — I knew I would deal with my own evolving relationship to Céline’s music, which meant giving an account of where I’d begun and how I felt as I went. But as I got further in, it became clearer how radically subjective all the researched questions really were. The sentimentality issue made my own sentimental life seem more relevant. Plus I was becoming ever more skeptical about “critical distance” — in some ways the book is an attack on that notion. I wanted to break that chasm down, to be more intimate with the reader.

It’s also a matter of craft: A well-told personal story can have more impact than a hundred reasoned debate points. It needs to be supported, so that it becomes more than anecdote, but those human details make it resonant and memorable. And when I asked for feedback, my trusted friends told me they wanted to hear more of that and fewer appeals to “expert” authority. I followed their wise counsel.

The book was partly an exercise in empathy. Do you think you would reach similar conclusions today if you were to write another 33⅓ volume on, say, The National, a band for whom you’ve expressed dislike?

As I said in that essay, I already have plenty of empathy for The National. I get their approach. It’s not far off from what I might do if I were a musician. My impatience with them is more about the execution — I feel they often assemble smart, worthy elements in fairly dull ways. So it wouldn’t be the same kind of exercise. But you’re right, the deeper one digs the more one understands. So yes, I could probably cultivate more of an appreciation for parts of The National’s practice that I don’t currently notice. But I don’t think its implications would be nearly as far-reaching. Which is why I feel like it doesn’t matter if I say I dislike them.

In the case of Céline, did her success and popularity make her easier to write about?

Popularity is a complex phenomenon, never easy to analyze unless you’re making lazy suppositions. But I’m not sure how I could have written a book about an obscure version of Céline Dion — it’s kind of a contradiction in terms. Céline the phenomenon is as much a subject of the book as Céline the person and the artist, and it’s what makes her a case worthy of book-length treatment, because it implies broader social meanings. If she were an unknown nightclub singer in Quebec, it might have been an article but never a book. It would be, “Why is this great singer not getting anywhere?”

You’ve suggested that we’re living in a “post taste” society. Does that mean concepts of guilty pleasure, hate-watching/listening, and ironic liking are now outdated?

I don’t actually say we live in a post-taste society — I’m saying it could look like that from the P.O.V. of a late-20th-century cultural observer. I think that taste is undergoing a big, fast-moving but long-arcing, unfinished realignment. But taste, as a social technology, has been operative since there’s been professional culture-making (at the least) and I don’t think it’s going anywhere. It’s more that the former categories of high-middle-lowbrow, obscurity/popularity, etc. don’t operate the way they did a little while ago. People migrate between them and don’t feel guilty or ironic in the same ways they did. On the other hand “hate-watching” is a kind of new way of articulating those contradictions. I don’t think that phrase existed a decade ago. “Post-taste” is suggested more as a thought experiment than as an earnest thing. A person would need to read the whole analysis in the new Afterword to get the tentative points, because it’s all in the details.

Were there any surprising takeaways from having contributing essayists respond to your book? Mary Gaitskill’s piece—which was perhaps the most critical of your work—was particularly great.

Mary’s writing has inherent fire, and she got in some good burns, but I like the way it came around to examining her own biases and prejudices in the end. I was most intrigued by the recurring theme in the essays about the paradoxes of trying to escape taste — that criticizing our elitisms can be another sleight-of-hand to reinforce them, and at the same time we need not to shut off our appreciation of great artistic power in the name of egalitarianism. Those are really tough knots to untie.

As a critic, do you feel a sense of responsibility to artists who are trying to make a living as musicians, even if you’re not a fan?

The responsibility I feel is never to treat artists as if they’re not fellow human beings. I feel a common cause with the whole enterprise, and I respect the effort and vulnerability of putting your creative work out there. But sometimes musicians feel like it’s your job to serve as an arm of their promotional work. My job is to create interesting cultural conversations. I work for the reader, not for you, though I hope you get something out of it.

What makes a great music critic? Aside from the contributors in the book, who are you a fan of?

All kinds of qualities can make a great critic, though the two biggest to me are probably sensitivity of attention and texture of voice. I’m a fan of a hundred of them. This isn’t a field I ever really consciously meant to join, just stumbled into, but it’s been such a lucky accident because it’s given me such a rich community of people to talk to, react to, learn from. It’s an underrated literary gold mine. The contributors are a great place to start, or the books of veterans such as Ellen Willis, Greil Marcus, Greg Tate, Simon Frith, etc. But so is your favourite blog. I don’t want to start naming more names or I’d exclude too many.

What’s the most impactful criticism you’ve ever received and learned from? Was it from a friend, an editor, a mentor, or a piece of fan/hate mail?

Can’t think of a singular moment. I’ve needed to be told to unpack my thoughts, not just to pile them up densely. I’ve needed to be told to be more frank and personal. I’ve needed to be called on moments of pretension or evasion or laziness. Pretty much always by friends. But I’ve certainly been informed by — and the book partly came from — hate mail that asked who was I to disagree about whether a record or concert was good. My answer is that I’m the one who can write about that experience entertainingly and informatively, but I wanted to find ways to write that didn’t suggest that their experience was invalid. Long ago I wrote a concert review of the Cranberries, for example, where I made a lot of jokes about what I saw as the gaucheness of their various schticks, and it pissed fans off who’d been at the show. I wouldn’t write it so glibly now. I’d try to account for it more thoughtfully, and to answer the “Who are you?” question at least in part.

Does it surprise you that your book has attracted teenage fans like Tavi Gevinson and Lorde, girls who didn’t grow up in the ‘90s Céline bubble?

Yes, in a delightful way. I’ve worried that using Céline as a focus might cause the book to date quickly but that doesn’t seem to be happening yet, thankfully. And I’m stunned to imagine I can pass anything useful to these brilliant young women who seem to me so far ahead of the worn-out routines already. I think it probably just gives them more confidence in the instincts they already have. Sometimes it’s good to have thoughts reinforced, and I’ve probably done some reading they haven’t done (as they’ve read things I haven’t, too!). It’s a fantastic unexpected gift that they’re interested and sharing it with people who are interested in them.

How do you think gender affects your criticism? Is that something you’re self-conscious of as a male critic?

Of course. The book is partly about trying to unlearn the male “authoritative” P.O.V. that I unconsciously absorbed from my reading as a young person, although I think coming from Canada, particularly from a working-class town (although my generation of my family had become comfortably middle-class), with an uneasy relationship to masculinity, had already made me wary of the kind of Ivy League white-guy dick-swinging that cultural criticism, especially rock criticism, can lean to. That said, I still struggle with making my voice as open and inviting as I want it to be rather than argumentative and didactic, and I think that’s partly a white-male thing.

In retrospect, I wish the original book had dealt with gender, race, and sexuality in a more head-on way — they are there, acknowledged, throughout the book, but really should have had more equal status with the class and cultural issues that are in the foreground. So I’m always learning. That’s one of the reasons I’m so grateful for the contributions by Daphne Brooks, Ann Powers, Sheila Heti, Drew Daniel, Jason King, and others in the new edition — I think they help redress that balance. And there are so many great people practicing criticism today, especially online, who are moving the consensus and making sure we all have these issues more at the fronts of our minds.

What are you listening to now? What bands or artists do you love?

There are always too many answers to these questions. LTAL contributor Owen Pallett’s new album In Conflict is probably my jam of the month — we became friends through his work, but I’m in awe of the personal, emotionally open but narratively complex breakthrough on this album, which makes everything before it seem like warm-ups by comparison. A real coming of age. I will take any opportunity to tell the world that Veda Hille (from Vancouver, BC) is the greatest contemporary songwriter you’ve probably never heard of, a keyboardist and vocalist whose work might remind you from moment to moment of Brecht-Eisler, Tori Amos, Brian Eno, or David Byrne, but mostly of nobody else ever. Poetry and laughter and science and tidal pull. Someone give her a Genius grant. But I love Taylor Swift and the Knowles sisters and Frank Ocean and Killer Mike too. I have lobbied for Destroyer for about 15 years and since Kaputt more people know I was right. Next, start listening to Bob Wiseman. I am a recent convert to the greatness of Stephen Sondheim — musical theater has been a slow grower for me. I will go to my grave waiting for Richard Buckner to win all the Grammys. I am happy people have started listening to Laraaji and Moondog and (is this true? I think it’s true) Nina Simone and Laura Nyro more lately. I was very sad that Invisible Man-bandage-wrapped Ontario new-wave-prog violinist Nash the Slash (Jeff Plewman) died this week. Country singer Iris Dement is probably the best at making me cry, which is part of the subject of my latest project in progress.

Then again, mostly I listen to podcasts, honestly. I like the companionship. I get to be on the Slate Culture Gabfest now and then, which is probably my most selfishly gratifying professional achievement of the past year.![]()

@carlzoilus