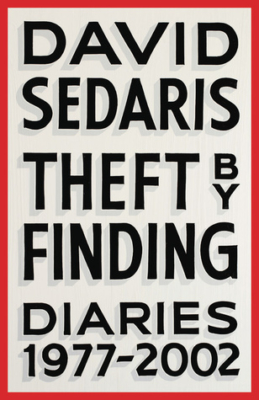

In one shining sliver of a moment, David Sedaris’s life, as noted in his new collection of diaries Theft by Finding, intersected with my own. In an entry titled “October 23, 2001, Allentown, Pennsylvania” I see not only my hometown but remember the day Sedaris came on one of his early book tours. When I saw the location of the entry, I cringed, imagining what bland element of the town was so notable that he had to jot it down. Instead, the entry was about a comment made by local hosting professors that had Sedaris laughing harder than he had in ages. With that I happily accepted Sedaris’s one-day perspective on my hometown over the one I built up over 18 years.

A funny thing happens when you devour 40 years of someone’s life, recounted day-by-day in simple, intimate terms. The memory of their life starts to take over the present of yours. This can only really happen if the diary achieves the seemingly impossible balance of being authentically written for no one’s enjoyment and still innately enjoyable to the reader. This may not seem surprising for Sedaris fans, who are used to wild and wry stories pulled from his life and family, but the writing in Theft by Finding is a different Sedaris. It’s the DVD commentary to the film we know.

Thankfully, that same sharp, honest observation is still behind his everyday notes, even if it isn’t crafted into polished narrative storytelling. Seeing what little things were deemed diary-worthy allows one to better understand his perspective as a whole. On October 17, 1985, the name of the newly elected Cherokee Nation leader, Wilma Mankiller, made the cut. On October 5, 1997, his entry includes an expression of annoyance over having to sit through yet another preview for Titanic: “Who do they think is going to see that movie?” In May 1998 he wrote of a single visiting friend who told him how a man he took to bed whispered to him, “Let’s pretend we’re cousins.”

A diary is a strange thing to review since only best friends, mothers, and that argumentative person on the subway are the only people who have authority to comment on how someone should be living their life. But when looked at as an piece of literature it reveals more, both in terms of style and substance. Sedaris is the first to note this, quite literally in the introduction. He cautions against what you’re not going to expect, namely exposition of his feelings and inner dramatics. A diary is a lesson in self, and the practice over times allows for one to better understand themselves. Sedaris skips the learning curve portion, which in the beginning he states was either boring, meth-induced or both. Some people were removed entirely based on their own request. A significant relationship and breakup is never mentioned directly, only clarified to Terry Gross on Fresh Air as the cause for an entry that begins with a list entitled, “Reasons to Live.”

Given the absence of extended talk of feelings and emotions, the big events that he did chose to include — the death of his mother, the realization that he’s in love, his sobriety, his first broadcast on the radio — are given as much word count as the stranger he witnessed at his beloved IHOP. For a diary, it isn’t very self-centered. But Sedaris wields a finely-tuned lens; even if it isn’t pointed inward, it is a wonderful way to see the world around him.

In the fall of 1985, while a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, Sedaris wrote, “Unfortunately I write like I paint, one corner at a time. I can never step back and see the whole picture. Instead I concentrate on a little square and realize later that it looks nothing like the real live object.” Theft by Finding is certainly a collection of tiny squares that, when taken in together, creates a very real, very alive work of art.![]()