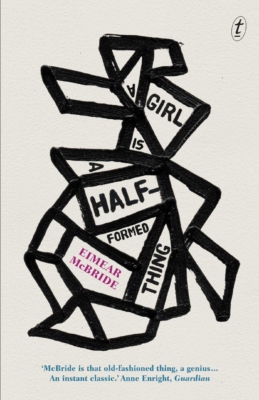

If a book’s description has the words “meditative,” “mundane,” and “stream of consciousness” in it, then I’m sold. So, when I read James Wood’s glowing review of Eimear McBride’s debut novel, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, needless to say I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it. The book tells the story of an unnamed Irish girl growing up without a father, with a stern “Mammy,” and with a brother born with a brain tumor — a ticking time bomb that hangs over the narrative — and follows her from childhood until the age of 20.

As a teenager, the protagonist is sexually abused by her uncle, and McBride focuses on the harsh, painful, and deeply uncomfortable coming of age of a girl who is used as a sexual object. The girl, in turn, uses sex as a means of power — it’s a way to protect herself from the pain of the world, and a way to stay in control of her destiny while living a chaotic life. McBride’s depiction of this complicated mindset is, to me, an important document of a how one might approach sex after being violated. Some of the graphic sex scenes (some consensual, others not) are hard to read, but relevant, as this raw honesty doesn’t seem to find its way into serious “literary fiction” as often as it should.

Another aspect of the novel’s noteworthiness is the modernist style in which it is written. Take the novel’s opening lines: “For you. You’ll soon. You’ll give her name. In the stitches of her skin she’ll wear your say. Mammy me? Yes you. Bounce the bed, I’d say. I’d say that’s what you did. Then lay you down. They cut you round. Wait and hour and day.” It is heartening to see a novel like A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing published in the current literary climate, even if the stream-of-consciousness sometimes borders on Joyce fan-fiction. The tone, the sharpness, and unorthodox delivery of McBride’s heady language is thrilling to read and decipher — especially if you are inclined to devour this kind of prose.

In other passages, however, the technique can feel forced, like in this section from the end of the book: “I the morning. I the day. When the air was. The air is. Today. today.” When compared to a thought the narrator has when she is still an early teen (“Those things that happen in your head when you are young and cannot fathom never being clean again.”) something seems off: Near the end of the novel, at age 20, wouldn’t the narrator have a more cohesive inner monologue?

Beneath the (sometimes successful, sometimes not) complexity of its style, McBride’s novel reveals an original portrait of a violated woman. If the style were better delivered (I don’t mean more eloquently or coherently, but with more logic and truth) this novel would truly be a classic. As it stands now, it is a much-needed document of an under-represented point of view in serious fiction.![]()